The Child as Adjunct

What a concept! #1

*Inaugural entry in "What a Concept!" an offshoot of the Fodor Variations. This companion series provides social commentary on conceptual theories, as opposed to focusing on the theoretical claims in isolation.*

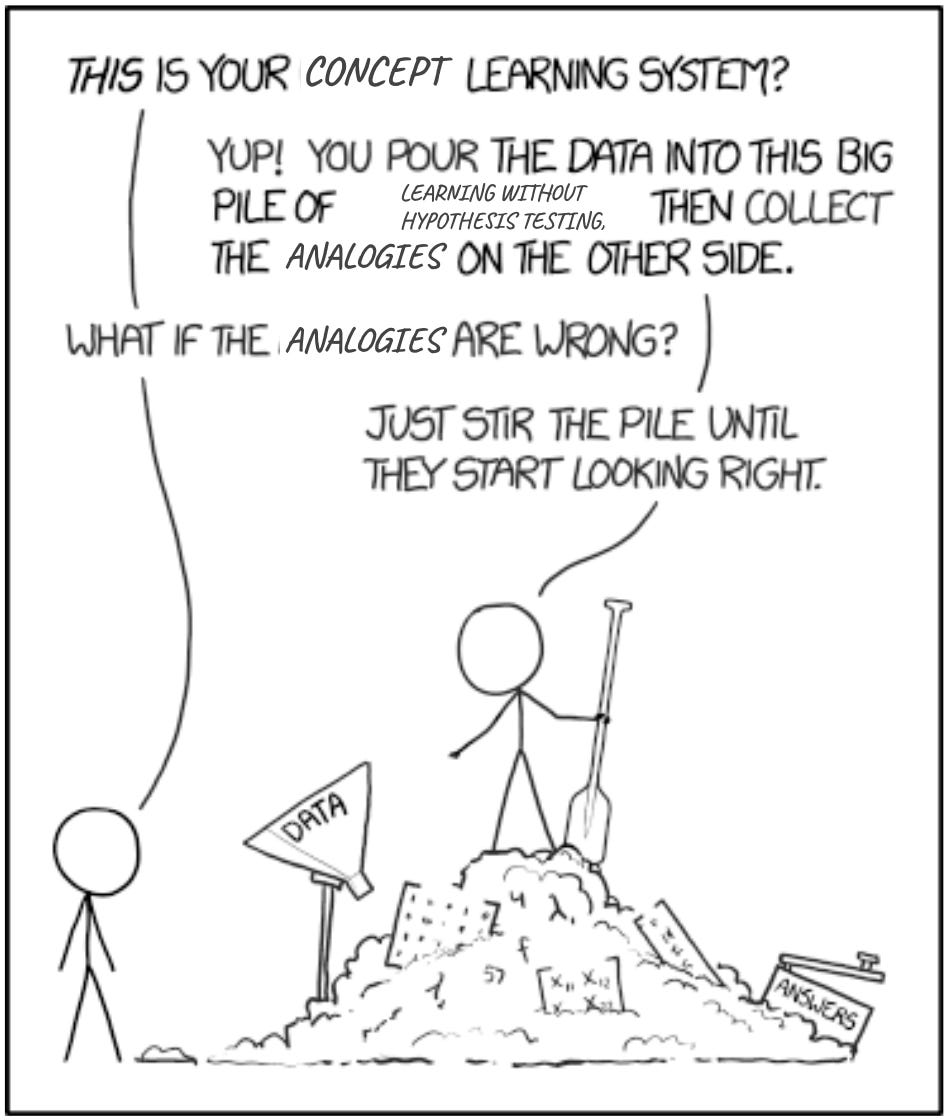

I like Theory Theory in theory theory but not in practice practice. It's a theory of meanings and concepts, yes, but also just a broader theory of learning. As a shorthand, I'd maybe describe it as a range of constructivist approaches to cognition. Theory Theories (TTs) can vary greatly, though, but they're often associated with the catchphrase "the child as scientist." While this metaphor is most heavily associated with TT, the idea behind it (and TT, really) can be found perhaps earliest and most explicitly endorsed in Piaget and Bruner: there's a meaningful relationship between how children and scientists learn. So meaningful, in fact, that thinking about one should shed light on the other. Developmental psychologists can look to the history of science (Nersessian, 1992; Smith et al., 1985; Carey, 1985), and maybe philosophers of science can even look to developmental psychology (Gopnik, 1996), and don't bother worrying about say, the sociology of science (as critics have pointed out; Faucher et al., 2009). Both scientists and children do need to learn about the world about them, and in the process they do alternately need to test their current assumptions, and, yes, seemingly learn words that go along with them. But lots of things are like lots of things, especially if you're one of those things (scientist) studying one of those other things (babies). As far as inspiration goes, I suppose you could do worse than the Doctrine of Signatures, but unless you're Galen I doubt it's very compelling as evidence.

What does TT say about how meanings and theories relate? It's hard to say generally because even individual theorists can at times switch between different levels of the analogy Bishop & Downes, 2002. I'll cautiously say that a popular view is that TT considers the meaning of a word to be the role it has within a theory, and so learning a word is to learn how it figures in said theory. Since it's not just learning the term in the theory, but it's role, which requires understanding other aspects of the theory (like relations to other concepts). Some, as in Carey (2009) , describe it more explicitly in this way through endorsing a Conceptual Role Theory interpretation. To learn what numbers are, for example, requires going from some simple theory which is wholly incapable of representing number (e.g., theories about object files or magnitudes) to a theory which can (i.e., integers) and ultimately allowing scientists to arrive at a theory of number which is consistent with some other theory more contemporary theory (e.g., mathematics (e.g., set theory) and semantics (e.g., model-theoretic)). That would mean that when I think thoughts about ONE I think about how it fits into a theory (e.g., how it's also ZERO + ONE) that young children cannot represent. These theories, being scientific and thus novel, presumably require proposing hypotheses one couldn't propose before. Certainly infants don't have the pieces laying in wait to think thoughts about CARBURETORS. Being scientific, they presumably allow for more or better detailed inferences which would be beneficial and allow for the creation of things like carburetors.

However, as we'll discuss elsewhere, it's entirely unclear how you could propose a hypothesis that you can't already think of. We'll get into the nitty gritty of this later, but instead of speaking abstractly, let's do something a bit obscene: go meta. If TT is true, and the meanings of a word is its role in a theory, then what's the right theory for the meaning of “scientist”? Such a theory would tell us what TT advocates mean when they use the catchphrase, following their logic. Based on the TT work I've read, it oddly seems like the working theory of scientist held by TT is that of a Tenure Track (TT) professor. However, there are many different theories "scientist" could figure in, and they need to be ruled out. Presumably a theory of what scientists are will have to start from a place of being descriptive, and, in the case of disagreement, likely have to be determined by the theory that covers the broadest range of data1. That's where science starts, after all, observing the world a forming a hypothesis, so if that's what scientists are doing too, then what theory of science should we go with?

Now, while I certainly don't disagree with Gopnik's assertion that scientists are big babies (Gopnik, 1996), I think my principal issue with equating scientist and children is that most scientists don't have time or resources to go on a grand quest for truth, as much as I'm sure they'd love too. Most academic scientists, in fact, are too busy trying to make ends meet. An estimated 74% of professors are adjuncts which are often paid less than $3,500 per course. Based on numbers alone, the best theory of "scientist" suggests that "scientist" does not typically mean tenured scientists. This would mean, sadly, the child as scientist is effectively stuck adjuncting and has no time to figure out whether "water" really means "H20" or "XYZ." Unlike tenured scientists, children have to focus on survival-oriented goals that are accomplishable within their limited resources. This means that upon encountering an obstacle, say, the meaning of a word like "cookie", they cannot wait until more experiments have been run, lead a seminar on whether one needs to learn "food" first, nor buy out of teaching2 for the semester to figure it out. They've got to eat right now, after all, and a fantastic meal in 6 months means little to someone who's died of starvation, similarly, a magnum opus is far less helpful if you've long been fired because you've shirked your teaching duties.

The issue, as I see it, is that the practice of science is intimately related to 1) one's goals' and 2) the resources at one's disposal, and the child is nothing like a tenured professor in this regard, to the point where the analogy may be in fact quite misleading. If, as TT suggests developmentalists can glean a lot from the practice and history of scientists, then it should not look to scientists like Charles Darwin as an example (e.g., Gruber & Barret, 1974). This is not to say their approach is worse, nor that there is not in some sense a spectrum. Only to point out that it suspiciously resembles a sort of an antiquated and romanticized view of science3, one which may distract TT professors from empathizing with the experience of most scientists. And, if they're trying to relate to kids, this may mean they're farther off than they imagine.

All of this ends up constraining how exhaustive4 children and adjuncts can be in their theorizing. It's harder for an adjunct to find time to focus on the only thing which will guarantee their continued stability within academia in the US: tenure. That's because tenure-track job searches rarely prioritize teaching ability/experience over whether applicants produce world class research5. But, of course, adjuncting is a teaching position, they're brought in to deal with the fact that demand for classes vastly outpaces the supply of tenure-track positions administrators deign to offer departments. Tenure track lines are expensive, and given that the economic situation is so dire adjuncts are willing to do the job for the hope that they can keep doing what they love (or bear), they're a far cheaper solution to the demand for courses. It's, in a sense, academic outsourcing and the problem with outsourcing, as I hope we can all appreciate, is that it incentivizes businesses to keep things exactly as they are (or worse) so as to not jeopardize their cheap labor pool. If life were better for adjuncts, it would cut into profits, but the desire to maximize profits is what led to the creation of poorly-paid adjuncts in the first place. Given the relative cheapness of pedagogical labor, universities really stand more to gain more from TT professors if they focus on bringing in the most grants. Naturally, this also can result in a bad time for TT profs. Bla bla bla, surplus value, my point here is this set up isn't really helping most of us out, even those theoretically "winning" in the academic game.

A defender of TT (either one), may point that, sure most scientists aren't tenured, but tenured scientists have the most power - that is, if we charted the causal force of each scientist, they'd have the most impact on change. So, if our theory of "scientist" identifies it with the role of adjunct, it's in fact not capturing the relevant causal structure and is a worse theory - it's not distributing the weight of causes properly. This, of course, neglects to engage with what is really the present point - such tenured scientists would not be in a position to have greater impact if they did not have the support that they do from the untenured horde that standing behind them. Typically when we talk about concepts, we stick to simple examples - color, common animals, food. We avoid these political cases like scientist, and so it's easy to pretend these theories say a lot more than they do. When we want to know what a scientist is, we don't turn to a single theory - until fairly recently we believed it was important for scientists to be white (DALL-E/GPT-4 seems to be stuck in this era, without injecting "ethically ambiguous" into prompts). We can't even know that we all tune into the same ones, and yet, we can all still talk about them as though we do, and use them in sentences like "I am a scientist." If we want to know more, and are academically inclined, we may turn to history, or anthropology and sociology. We won't just tabulate which words co-occur with scientist or attend to chains of inferences most people make about them, and yet this is easier to ignore when limiting oneself to RED in my opinion.

Yes, scientists do learn, and they do use new words in the process, but so do baristas, influencers, politicians and whatever economists are. Everyone learns and names things in the process, and, yes, I do believe we all do so in a remarkably similar way - in that sense I am in complete agreement with some advocates of the metaphor. The difference is that the scientists proposing these theories have immense support in their learning, that's what makes them scientists: they're provided accomodations and resources for their learning. Someone may reply, but that's not a problem for the child as scientist view, yes, they're all big babies: baristas, influencers, politicians, and especially economists, all of 'em. But, if that's true, then why pick and stick with a metaphor which singles out a class of people for whom learning is the survival constraint? At best, it's half of the piece of the puzzle. Just as one shouldn't conclude what makes one happy just from studying happy people6 and one shouldn't imagine that learning is analogous to how those with the most time and support to do so go about it.

Small closing caveat: My point in saying any of this is not to claim I somehow am superior to these theorists. I don’t believe that in the slightest. It’s also not in any attempt to “cancel” them or whatever. I just think it’s interesting to think about and talk about, and I think it could be important long-term to the health of the discipline to be more open to such discussions. Anyway, I don’t think any of the people I mentioned are bad or unethical, I think they’re human and as such as shaped by their environment as everyone else. We should be able to talk about that :)

If it's good enough for democracy, it's good enough for making lawlike generalizations, I always say.

In the process, creating need for an adjunct to replace them - one which will, you guessed it, be paid for less, be given zero benefits. I could go on!

And, well, Great Man Theories of history

As this series develops, I will make clearer that what I mean by exhaustivity in this context is really something more like holism, but I don't think we're ready for that just yet and exhaustive gets the job done.

Which only happens in the west btw, and even then really mostly the US. It’s commonly assumed he rest of the world rarely figures in “world class,” it turns out.

Unless you're a positive psychologist, I suppose.